Later, warmer and greener autumn as climatic change comes to North Germany

Evaluations carried out by the North German Climate Office at the GKSS Research Centre in Geesthacht reveal how the North-German autumn could change with tomorrow’s climate.

The start of November is normally the middle of autumn in North Germany: the heating season has begun, the many-coloured leaves are falling from the trees and it will soon be time to harvest the curly kale. But how is autumn going to look in the coming years?

Evaluations carried out by the North German Climate Office at the GKSS Research Centre in Geesthacht reveal how the North-German autumn could change with tomorrow’s climate.

It can stay warmer for longer

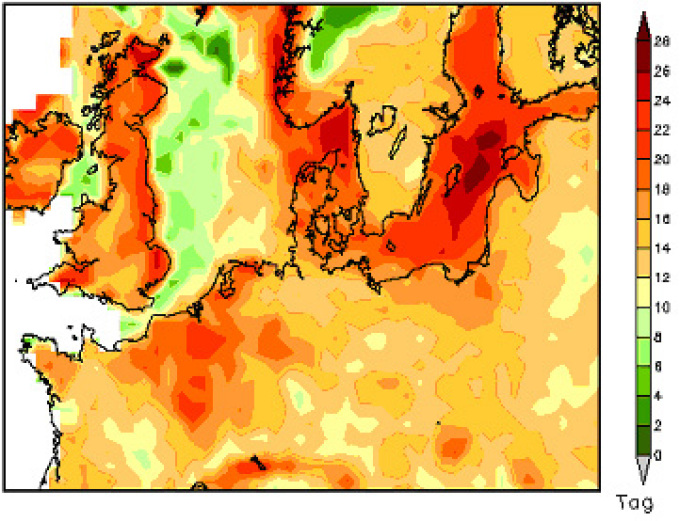

The time shift of the first cool autumn day (below five degrees Celsius) towards the end of the century (2070-2100) compared to today (1960-1990).

This climate calculation is based on a relatively small increase in greenhouse gases.

According to various regional climate calculations, it is plausible to expect autumn in North Germany will arrive two to three weeks later in the year at the end of the century than now. For example, the first cool autumn day, with temperatures below five degrees Celsius, could arrive 14 to 24 days later than currently.

The calculations also indicate that by the end of the century we could be seeing around three additional summer days with temperatures in excess of 20 degrees Celsius between September and October. On average, autumn in North Germany could be between two and 4.5 degrees Celsius warmer than previously.

Thanks to these changes, holiday destinations on the North and Baltic Sea coasts will also appeal to larger numbers of holidaymakers during the autumn holidays. On the other hand, shortages of drinking water and health hazards resulting from thermal stress will extend into autumn.

“In around 50 years, September in the metropolitan region of Hamburg and on the coasts of the North and the Baltic Seas will be as warm as August is today,” says Dr. Insa Meinke, Head of the North German Climate Office at the GKSS Research Centre Geesthacht.

But the end of autumn will probably continue to be marked by stormy and rainy weather: at the end of the century, we can expect up to 30 per cent more rain in November, as well as wind speeds up to six per cent greater than today’s.

Numerous changes to the ecosystem possible

If the temperatures really do change to this extent, then a large number of further changes will be caused for many animal and plant species. The temperature increase to date in North Germany of 0.8 degrees Celsius over the last century has already had a number of effects, including vegetation periods that last around ten days longer than they did 40 years ago. The possible warming in future will lead to the leaves changing colour correspondingly later. The North Germans will also have to wait up to four weeks longer for their curly kale in future. Assuming that the farmers wait until the first day of frost in autumn, the curly kale harvest in North Germany could move back by between ten and 28 days by the end of the century.

Changes in the routes of migratory birds are already being observed throughout Europe. Some migratory birds, such as cranes, already remain in North Germany all year round in mild years. The range of heat-loving plant species could shift towards the north, while local species extend their range further into Scandinavia,” says Dr. Insa Meinke of the North German Climate Office of the GKSS Research Centre Geesthacht. “Predicting the future of an ecosystem in detail, however, is still extremely difficult due to its complexity. Nonetheless, the effects could be massive,” emphasizes Meinke.

Possible reduction in heating costs

According to various calculations, there may be around four to seven fewer days of frost in autumn at the end of the century than there are now.

The calculations of the Geesthacht Research Centre’s North German Climate Office assume that central heating systems in the north of Germany will be switched on four weeks later than at present. The consequence would be lower energy costs, as central heating systems are usually first switched on after a cold period of three consecutive nights with temperatures of below 12 degrees Celsius. The calculations indicate that by the end of the century, in comparison to today, such cold periods could arrive between eight and 28 days later.

“Although we can see certain positive aspects to the effects of climate change on autumn in our region, the scenarios for the winter and summer are going to present us with much greater challenges,” says Meinke. These include in particular a possible severe reduction in summer rainfall and an apparently dramatic increase in winter precipitation, as well as a possible increase in the intensity of winter storms. These changes will put humanity and ecosystems under massive pressure to adapt. Meinke sums up: “Taking a more differentiated view of anthropogenic climatic change will pay off.

Scientific background and outlook

The predictions regarding future autumns in North Germany are based on various regional climate calculations which have been carried out at the German Climate Computing Centre in Hamburg and in the course of various EU projects in which the GKSS Institute for Coastal Research participated. These calculations are based on various concentrations of greenhouse gases. For this reason, all figures quoted are ranges within which the North German climate could change in the future.

The North German Climate Office is the contact partner for questions regarding climate change in North Germany. The results of this study were generated during work on a climate atlas for North Germany which is currently being carried out in the North German Climate Office. This climate atlas is intended to provide decision-makers in North Germany with up to date insight into how their local climate could change in future. Publication of the complete atlas is planned for spring 2009.

The GKSS Research Centre Geesthacht’s North German Climate Office was established as a result of a deficit that had become apparent in communications between climate researchers and the users of research results. These users are decision-makers at authorities and agencies, and in politics and in business. They include representatives involved in coastal protection and from the agriculture, energy, fisheries, tourism and health sectors.

Subsequent to the successful launch of the GKSS Research Centre Geesthacht’s North German Climate Office, the Helmholtz Association established a Germany-wide network of regional climate offices in 2008.

The University of Hamburg has established the KlimaCampus Hamburg as part of the Federal Clusters of Excellence Initiative (CliSAP). The North German Climate Office is being expanded in line with this. As part of the excellence initiative, a climate report for the metropolitan region of Hamburg is currently being prepared with substantial help from the Geesthacht climate researchers — with the first results expected at the end of 2009.