The Food Chain’s Influence on Phytoplankton Population

The frequent occurrence of phytoplankton in North Sea coastal waters can also be explained by relationships within the food chain. Assumptions thus far have always relied mainly on chemical and physical influences. One scientist at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Geesthacht has now developed a new hypothesis that can be reproduced through computer simulations.

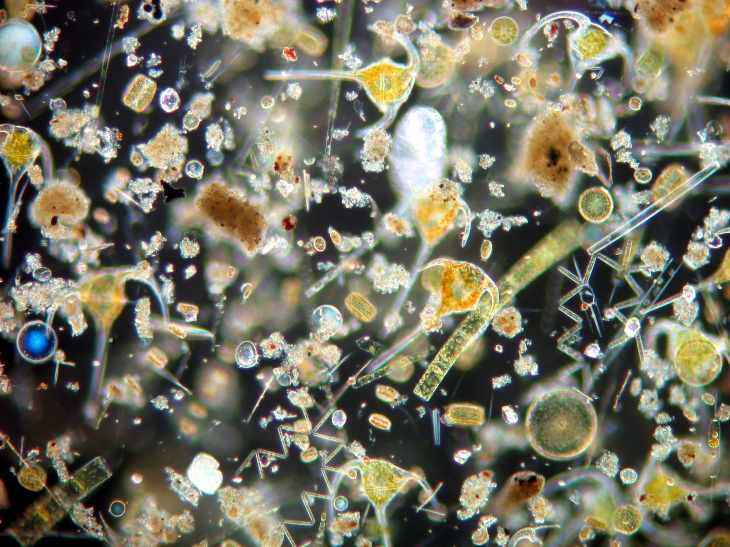

Plankton community. Photo: Annegret Stuhr/GEOMAR (CC-BY 4.0)

Anyone who has ever visited the North Sea knows that the water here is very rarely bright blue. Most often it is rather brown and relatively cloudy. The turbidity arises from mineral and organic particles in the water. That is why very little light penetrates the water. It is therefore even more astounding that, especially in turbid coastal waters, chlorophyll is found in high concentrations. This is visible in satellite images. Chlorophyll, the green colour in leaves, is an indicator here of single-cell algae or phytoplankton. Phytoplankton require light as energy, just as humans need food. So, why is there such a considerable accumulation of plankton despite so little light?

Prof Kai Wirtz, head of the Ecosystem Modelling Department at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Geesthacht’s Institute of Coastal Research, has been grappling with this question. He studies the coasts, for which he develops and uses computer simulations. He noticed that the model results and the observed data did not correspond—particularly in regard to phytoplankton. Scientists normally searched for an explanation looking at the nutrient supply or water depth. “Until recently, it was mainly physical parameters that were integrated into the models. This includes daily dynamics such as ebb and flow, but also seasonal conditions, water mixing, waves, etc.,” Wirtz explains.

The scientist’s new approach is that biological factors need to be taken into consideration in the computer models in a much better fashion

Crustaceans like this specimen often regulate the phytoplankton population. Photo: Maarten Boersma/AWI

His thinking is that the turbidity in particular provides small fish with protection from predators. The more young, small fish live there, the more zooplankton—that is, animal plankton—is consumed. This in turn is good for the phytoplankton—the plant-based plankton: the zooplankton feeds off of the phytoplankton. The phytoplankton thus has fewer predators and can grow without as much disturbance. This food chain effect stays relatively constant throughout the year.

The main blooming season for algae in the southern North Sea is around April. Computer simulations that take this effect into consideration, however, predict a much stronger bloom in spring than is observed. This is why Kai Wirtz has incorporated another, new factor: diseases caused by phytoplankton viruses. He succeeded. The viruses offset the extreme concentration variations.

By incorporating the known chemical and physical factors as well as these two new factors—“turbidity fish” and viral diseases—Wirtz’s simulation results correspond exceptionally with the observed data. Similar to the turbid-dwelling young fish, viruses were also frequently documented in coastal waters. “Despite the agreement and the evidence that speaks in their favour, these are merely hypotheses—the results would first need to be checked in a very complex series of measurements and field studies,” the scientist explains.

Publication

The paper was published in the online magazine PLOS ONE:

Wirtz KW (2019) Physics or biology? Persistent chlorophyll accumulation in a shallow coastal sea explained by pathogens and carnivorous grazing. PLOS ONE 14(2): e0212143.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212143

Contact

Helmholtz-Zentrum Geesthacht

Phone: +49 (0)4152 87-1513

Fax: +49 (0)4152 87-2020

E-mail contactInstitute for Coastal Research

Helmholtz-Zentrum Geesthacht

Phone: +49 (0)4152 87-1784

Fax: +49 (0)4152 87-1640

E-mail contact