Forests significantly influence the global mercury cycle

Plants and their leaves are believed to play a key role in intercepting human-made emissions of harmful mercury - according to a new study in the journal Nature Geoscience, in which scientists from the Helmholtz Center Geesthacht (HZG) are involved.

The IPEV monitoring station at Amsterdam Island (France, Indian Ocean). Photo credits: Isabelle Jouvie

A new study, led by researchers from the CNRS, the University Grenoble Alpes, and international collaborators shows that the atmospheric pollutant mercury shows similar seasonality as the greenhouse gas CO2. Atmospheric CO2 levels fluctuate seasonally as vegetation takes up the gas through leaves to produce biomass. Consequently, CO2 levels are lower during summer compared to winter. By comparing mercury observations at 50 forested, marine, and urban monitoring stations, the study published in Nature Geoscience (March 26, 2018) finds that vegetation uptake of mercury is important at the global scale. The researchers estimate that the biological mercury pump annually sequesters half of all global anthropogenic mercury emissions.

"We estimate that vegetation can temporarily store half of all anthropogenic global mercury emissions annually," says co-author Dr Ralf Ebinghaus, environmental chemist at the HZG. Dr Johannes Bieser, environmental scientist at the HZG and also co-author adds: "This publication has now brought a process into focus that was previously underestimated."

Mercury Cycle

The IPEV monitoring station at Amsterdam Island (France, Indian Ocean). Photo credits: Isabelle Jouvie

Each year industrial activities emit between two and three thousand metric tons of mercury into the atmosphere. With a long atmospheric lifetime of about 6 months, mercury emissions spread across the globe. What goes up must ultimately come down and this also applies to mercury. It has long been thought that atmospheric mercury deposition is predominantly by rainfall and snowfall, and monitoring networks measure mercury wet deposition worldwide. A slowly increasing number of experimental, field and modeling studies has suggested that plant leaves can also directly take up gaseous elemental mercury from the atmosphere. In fall, leaf mercury is then transferred to the underlying soil system by leaf senescence. Yet, the importance of this alternative deposition pathway, at the global scale, has never been fully appreciated.

Observations Worldwide

Mace Head. Photo: HZG/Ralf Ebinghaus

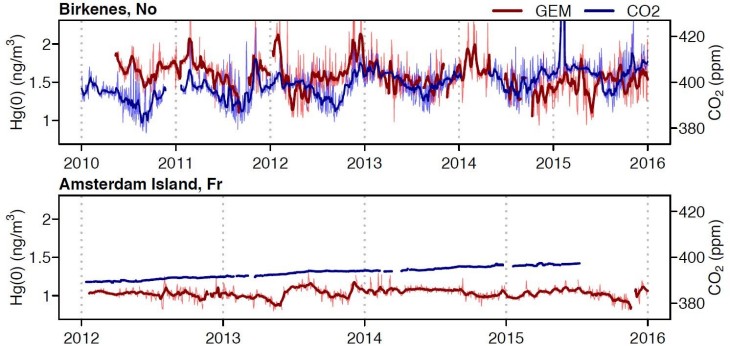

To understand if leaf uptake of atmospheric mercury is important on the global scale, Martin Jiskra and Jeroen Sonke, from the Géosciences Environnement Toulouse laboratory (CNRS / UPS / IRD / CNES), teamed up with scientists who monitor atmospheric mercury and CO2 levels across our planet. CO2 has a well-known seasonality with concentration minima in late summer, at the end of the vegetation and leaf growth season, and higher levels during winter. To their surprise, the researchers found that mercury and CO2 show similar seasonal variations at five forested monitoring stations in the Northern hemisphere (see Figure). Observations of mercury and CO2 made at Amsterdam Island by Aurélien Dommergue and Olivier Magand from the Institut des Géosciences de l'Environnement (CNRS / UGA / IRD) and by Michel Ramonet and Marc Delmotte from the Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l'Environnement (CEA / CNRS / UVSQ) turned out to be key in identifying the role of vegetation. At the Amsterdam Island station (see Photos), operated by the French polar institute Paul Emile Victor and surrounded by 3000km of Ocean in all directions, both mercury and CO2 show near-zero seasonal variations (see Figure). As part of this research Dr. Ebinghaus is responsible for a high-resolution long-term series of measurements at Mace Head - the longest measurement series available in temperate latitudes. From the HZG also Dr. Bieser was involved in the study - the environmental scientist supported the work with model studies.

Gaseous elemental mercury (GEM, red) follows seasonal CO2 (blue) variations at the forested site of Birkenes (Norway), reflecting leaf uptake of atmospheric mercury. The effect is absent at the oceanic site of Amsterdam Island (France) in the Indian Ocean. The study finds leaf uptake of mercury to be a globally important pathway of atmospheric mercury deposition.

Next, the researchers turned to atmospheric monitoring databases from EMEP, AMNet and CAMnet, examining seasonal mercury observations for another 43 sites globally, but for which CO2 observations were lacking. They found that the amplitude of seasonal atmospheric mercury variations is largest at inland monitoring sites away from the coast. At all of the terrestrial sites they found strong inverse correlations between satellite observed photosynthetic activity and mercury concentrations. At urban monitoring stations the correlations were absent, and mercury seasonality controlled by local anthropogenic mercury emissions. The researchers conclude that vegetation acts as a biological pump for atmospheric mercury and plays a dominant role in the observed atmospheric mercury seasonality. By comparing the 20% amplitude of seasonal mercury variations to the known amount of mercury in the atmosphere (~5000 metric tons), they estimate that each year about 1000 tons of mercury is sequestrated in vegetation via leaf uptake. This amount is equal to half the annual global anthropogenic mercury emissions. They also suggest that the documented 30% increase in global primary productivity over the 20th century has likely enhanced uptake of atmospheric mercury, thereby practically offsetting increasing mercury emissions. Although leaf uptake removes mercury from air, autumn litterfall transfers the sequestered mercury to soils. Soil mercury ultimately runs off into aquatic ecosystems including lakes and Oceans where the mercury bioaccumulates to toxic levels in fish. "Of course, this is not just a threat to marine life, but to the entire food chain," Dr Ebinghaus.

The research was funded by H2020 Marie Sklodowska-Curie MEROXRE grant No 657195, European Research Council MERCURY ISOTOPES grant No 258537, IPEV programme 1028 GMOSTRAL, and the FP7 Environment GMOS grant No 265113.

Contact

Institute for Coastal Research, Department Matter transport and ecosystem dynamics

Phone: +49 (0)4152 87-2334

E-mail contact